THE LITERATE WHISTLER

- whistlersoceity

- Jul 1, 2021

- 4 min read

DANIEL E. SUTHERLAND: LETTERS FROM AMERICA

James Whistler has been the target of many accusations and slanders, but none seems more ridiculous than the suggestion that he was not well read. A clear statement of this misguided notion comes from Mortimer Menpes, one of Whistler’s most dedicated followers. The Master, Menpes asserted, “read very little—I never saw him read a book.” Time to expose this canard.

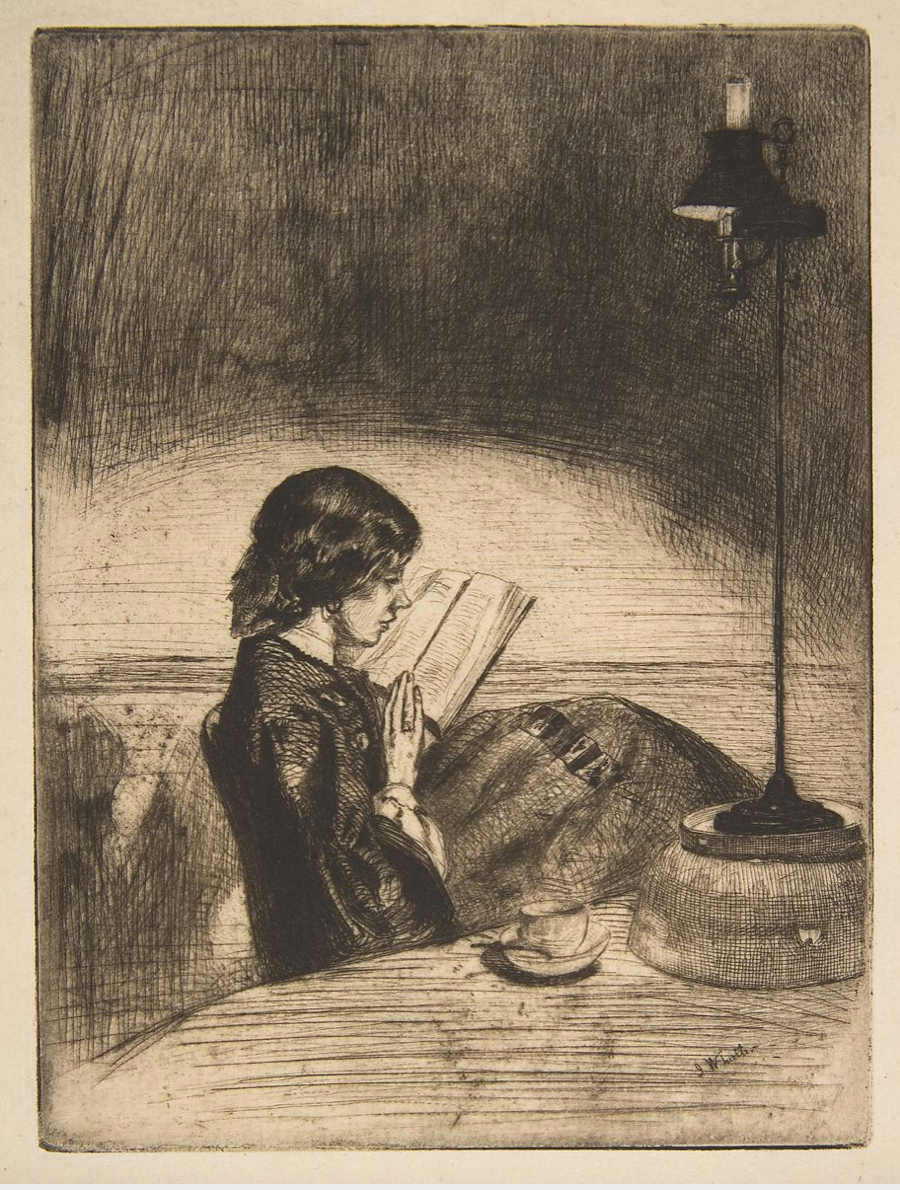

To begin with, Whistler was reared in an extraordinarily literate family. An early etching, done in 1859, shows his sister Deborah reading by lamplight. Not counting the Bible, which Anna Whistler required of all her children, Jemie was reading the novels of James Fenimore Cooper by age nine. A year later, he became immersed in a biography of Sweden’s Charles XII, very likely the one written by Voltaire. At age fourteen, he devoured a book about the Italian Renaissance and Sir Joshua Reynolds’ magisterial Discourses on Art, the latter being a Christmas present from his father. With that sort of grounding, and considering Whistler’s inquisitive mind and creative instincts, reading became a lifelong habit.

Like most of us, he was drawn mainly to subjects that interested him. Whistler did not, for example, read newspapers with any regularity, even though he always seemed well informed about current events. Symptomatic of his instinct for viewing the world with a “painter’s eye,” he preferred fiction and poetry. He confirmed his preference for novels at West Point. Besides Cooper, whom he continued to enjoy, he added Walter Scott, Samuel Butler, Elizabeth Southall, Oliver Goldsmith, and Charles Dickens. Menpes insisted that Whistler “could find no excuse for Dickens,” but that is nonsense, there being no greater literary influence on him. Whistler sketched scenes from the Englishman’s novels; colourful phrases and the names of memorable characters became part of his vocabulary. While working in Washington, D.C., following his dismissal from the military academy, Whistler bestowed Dickensian names, including Micawber, Heep, Swiveller, and Esmeralda, on several cronies, no doubt according to their personalities. He thought of himself as Sam Weller, the clever Cockney from The Pickwick Papers. In later years, his enemies became Pecksniffs and Podsnaps.

Whistler enjoyed French literature, too. The landmark novel À Rebours (1884), by Joris-Karl Huysmans, introduced him and the world to the Symbolist movement. He also read Huysmans’ more scandalous La Bas and savoured several other Symbolist writers and poets, including Francis Viele-Griffin, Octave Mirbeau, and Stéphane Mallarmé. He became dear friends with Mallarmé, whom he trusted to translate the Ten O’Clock Lecture into French.

Mallarmé had earlier translated the poems of Edgar Allen Poe, another Whistler favourite, whom even Menpes acknowledged had influenced Whistler’s thinking “immensely.” Other poets we know him to have read were Thomas Hood, John Gray, Algernon Swinburne, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Robert de Montesquiou, and Charles Baudelaire. Whistler read Baudelaire’s essays and reviews, too, but one of his poems, The Red-Haired Beggar Girl, very likely helped inspire one of Whistler’s most famous paintings, Symphony in White No. 1, better known as The White Girl. Similarly, a Rossetti poem, Jenny, may have prompted a Whistler etching, Weary.

Two other literary connections are less speculative. A portrait of Maud Franklin as “Effie Dean,” the unwed mother in Scott’s Heart of Midlothian, was done when Maud was pregnant with her first child, in 1876. A few years earlier, the heroine of a poem by Poe inspired Annabel Lee. So much for Whistler’s aversion to “story-telling” in painting.

It is unclear how much of Shakespeare Whistler read. He was thoroughly familiar with the plays, although, in this case, familiarity seems to have bred laughter. More than one of Whistler’s friends heard him expound on the “practical impossibility” of performing the Bard’s plays. He thought their “poetic power” too boundless for the stage.

We have a good idea of the scope of Whistler’s readings because much of his personal library has survived in the Special Collections of the University of Glasgow Library. In addition to much history and books about art and artists, numerous novelists are represented. Besides those already mentioned, one finds the work of Bret Harte, George Moore, Theodore Dreiser, Honoré de Balzac, Émile Zola, Théophile Gautier, Bram Stoker, Walter Besant, Eliza Humphreys, Edmund Gosse, Margaret Oliphant, and Henry James. We also know that some books Whistler is known to have read, including James’s The Spoils of Poynton, are missing from the collection.

So, to say, as some have done, that Whistler rarely read a book sorely underestimates his breadth of knowledge. No one could have been as riveting a conversationalist, as we know him to have been, without being well read. His facility with language as a writer also marks him as someone who had learned from the very best authors and poets. The Ten O’Clock, for instance, is filled with literary allusions, turns of phrase, and ideas taken from other works, not least the Bible.

Interestingly enough, Whistler has himself been the subject of poetry and a character in novels, in both his own time and the 20th and 21st centuries. That topic, however, must be explored on another occasion.

IMAGES

James McNeill Whistler, Reading by Lamplight, 1859, Etching and drypoint

James McNeill Whistler, Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl, 1862, oil on canvas, Harris Whittemore Collection

James McNeill Whistler, ‘Arrangement in Yellow and Gray’: Effie Deans, c. 1876 - c. 1878, oil on canvas, Rijks Museum Collection

We continue to be grateful to Emeritus Professor Daniel Sutherland for his outstanding contribution to the Whistler Society.

Comments