JAMES WHISTLER, EDGAR ALLEN POE, AND THE “SCIENCE” OF ART

- whistlersoceity

- Nov 30, 2021

- 4 min read

DANIEL E. SUTHERLAND: LETTERS FROM AMERICA

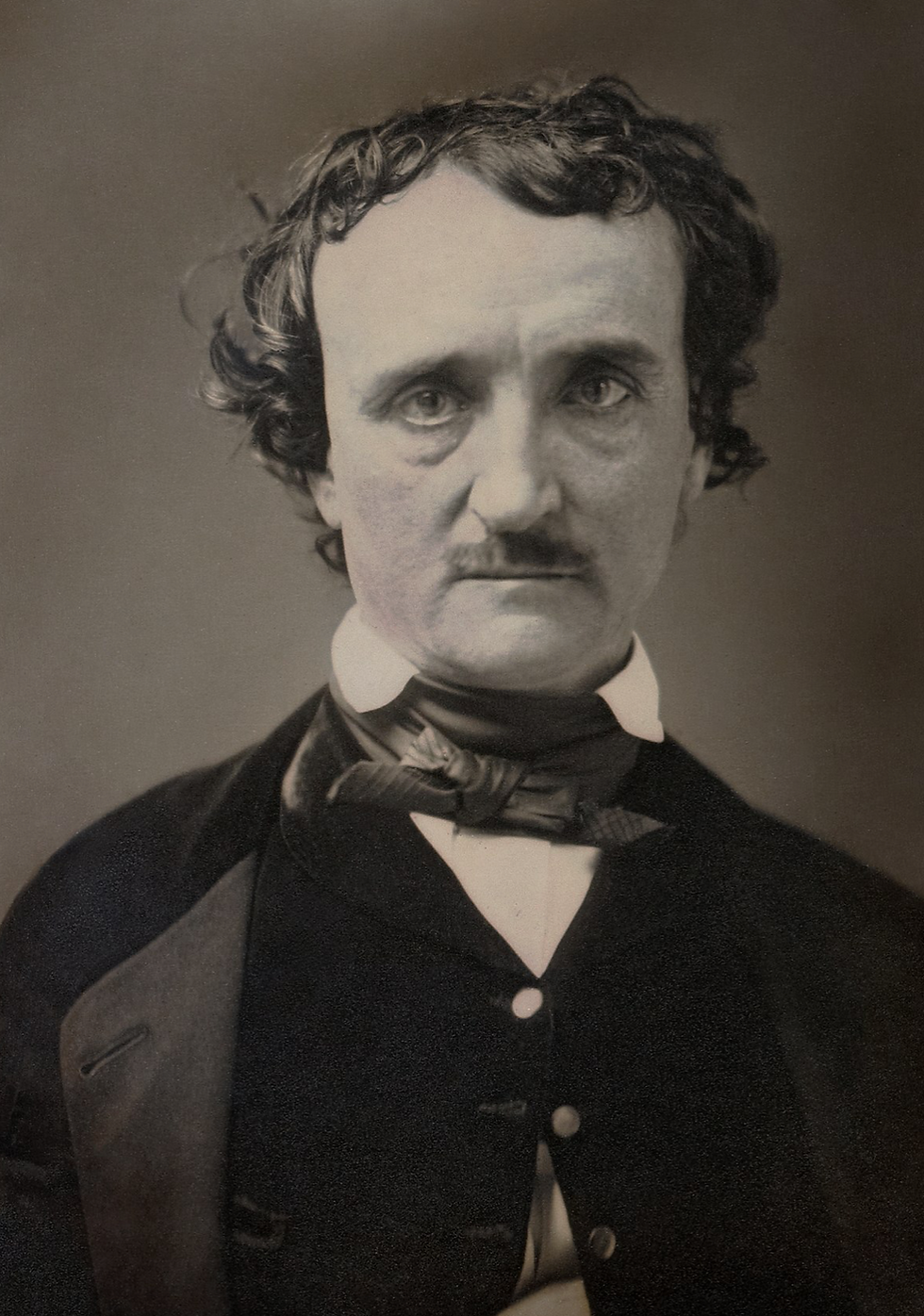

James Whistler and Edgar Allen Poe rank as two of West Point’s most famous failures, at least as potential army officers. Whistler was dismissed from the Academy for both academic and disciplinary failings, Poe mostly for the latter. Whistler at least survived for three years as a cadet; Poe lasted less than one year. The two men never met. Poe died in 1849. Whistler, aged fifteen, had recently returned to the United States after living for six years in Russia and England.

When Whistler first read Poe’s work is uncertain, though it was most likely at West Point, where the poet already ranked as a legend. Whistler would have thrilled to Poe’s tales of horror and suspense, especially a story like “The Fall of the House of Usher,” in which the main character is an artist. The poetry, too, drew Whistler, just as it did such literary friends and influences as Charles Baudelaire, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Algernon Swinburne, Stephane Mallarme, Robert de Montesquieu, and Oscar Wilde.

Poe’s ideas about art, nature, and beauty, expressed in such essays as “Nature and Art,” “The Philosophy of Furniture,” “The Poetic Principle,” “The Landscape Garden,” and “The Philosophy of Composition,” also caught Whistler’s attention. Indeed, several of Poe’s essays helped to shape Whistler’s own ideas about art in the late 1860s and early 1870s.

To begin with, Poe proposed that Nature is imperfect but can be improved by the “artist.” Beauty alone, he declared, should be the purpose of art, and while it must serve “noble” ends, it should never promote moral values, facile emotions, or political sentiments. Art should avoid the concrete in favour of the atmospheric and ephemeral. Poe’s favourite paintings were “landscapes of an imaginative cast.” In portraiture, he preferred idealized pictures of beautiful women. Poe also disdained fashionable whims and deplored the public’s aesthetic tastes.

Sound like anyone we know? But there was something more. Deeply impressed by the scientific advances and debates of his own day, Poe drew on the imaginative power of science for his fiction. His tales and stories are filled with references to scientific phenomenon. His fictional detective C. Auguste Dupin preceded Sherlock Holmes in the use of deductive reasoning. Poe even thought of writing as a rational process, governed by uniform laws and based on immutable principles. A poet, like an engineer, he insisted, must think in precise, deliberate terms. A poem or story had many moving parts—plot, characters, place, situation—but the whole must be calculated to create a single dramatic effect through “absolute truth of the entire design.” Nor did it arise from a sudden burst of inspiration, but only from careful construction. It unfolded “step by step, to its completion, with the precision and rigid consequences of a mathematical problem.” Elsewhere, Poe wrote of the “undeviating principles which regulate all varieties of art; and very nearly the same laws by which we decide on the higher merits of a painting.”

As the son of an engineer, Whistler understood. In 1867—coincidentally, the same year he began his painting Annabel Lee, the title of a Poe poem—Whistler abandoned the lavish colours of his earlier paintings to concentrate more on line and harmony. His solution, as it happens, echoes Poe’s essay “The Philosophy of Composition.” In explaining why he constructed his poem “The Raven” around a single haunting refrain, Nevermore, Poe emphasized that “repetition” and “variation” of the word held the poem together and produced a memorable climax. Applying this idea to painting, Whistler saw that a single colour, “the true colour,” like a literary refrain, could achieve the same ends. It was how Japanese artists, whom he already revered, “embroidered” a canvas, with “the same colour reappearing continually here and there like a thread . . . the whole forming in this way an harmonious pattern.”

In 1878, Whistler articulated many of Poe’s ideas in “The Red Rag,” but he required more time to appreciate fully the science that united them. He mentioned the “science of colour” in an 1872 letter to Henri Fantin Latour and spoke of the “painters science” in 1880, but not until “The Ten O’Clock” lecture, in 1885, did Whistler espouse the science of art. The lecture shows the influence of many and varied people on his thinking, but one hears Poe whispering to him throughout. Even as Whistler spoke of the “painter’s poetry,” he extolled “the science of the artist.” He insisted that art, and especially painting, was a science, and that the beauty of nature could be revealed only by applying scientific principles. “Nature,” he explained, “contains the elements, in colour and form, of all pictures, as the keyboard contains the notes of music. But the artist is born to pick, and choose, and group with science, these elements, that the result may be beautiful—as the musician gathers his notes, and forms his chords, until he brings forth from chaos glorious harmony.”

That Poe also believed in the intimate links between language and music, defining poetry as the “Rhythmical Creation of Beauty,” would have pleased Whistler—scientifically speaking, that is.

We continue to be grateful to Dan Sutherland for his Letters from America. They originate from his notes and research for his forthcoming book which will explore the enduring influence of James McNeill Whistler and the lives of those he knew and inspired.

Comments